- Alarmist claims that millions will starve due to climate impacts on food production seem to have no evidentiary basis.

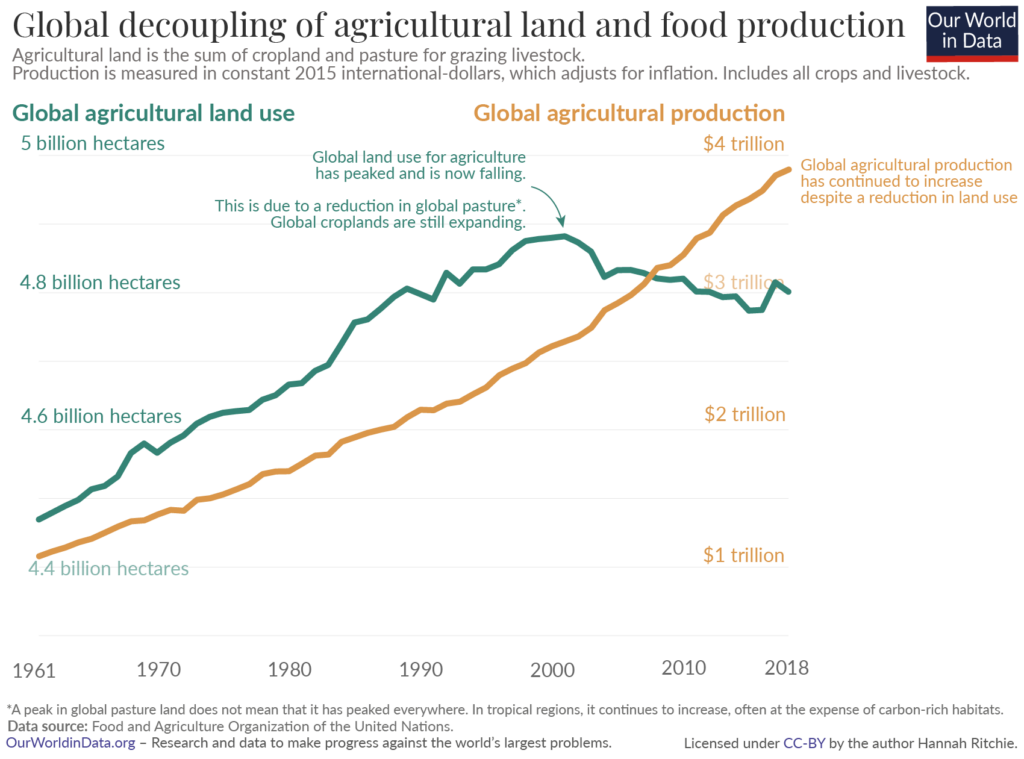

- In recent times, food production has increased using less land.

- Policies aimed at reducing climate impacts such as withdrawal of fertiliser have had far more damaging impacts on food production than anything climate change related.

The argument for radical climate policies is often based on the claim that climate change is having an impact on the world’s capacity to support industrial agriculture. According to Extinction Rebellion founders Roger Hallam and Gail Bradbrook, billions of people are going to starve, and survivors will have to resort to cannibalism. Both claim that their fears are based in science. But despite this claim having been challenged by scientists, other scientists support the pair’s organisation, which also enjoyed significant support from politicians and the UK government, which adopted its demands for Net Zero and a Climate Assembly.

Though such obviously extreme views are irrational, institutional science also produces alarming claims. A 2016 study published in The Lancet used models of climate and agricultural production to estimate that by 2050, climate change ‘will be associated with 529,000 climate-related deaths worldwide’, and that climate policies ‘would reduce the number of climate-related deaths by 29–71%, depending on their stringency’. Half a million deaths would of course be a major concern, but at four orders of magnitude smaller, it represents a far less serious problem than the fears of Extinction Rebellion activists, and on a global scale it represents a global mortality risk factor between homicide and malaria. A serious problem, but one which would not typically require global policies of the kind climate advocates propose.

Such studies have been based on computer modelling of highly complex interactions between society and the environment. What evidence is there that climate change is having an impact on agricultural production?

According to research on this topic, the amount of land used in agricultural production worldwide peaked in the 2000s and has been falling slowly, despite significant increases in productivity. At face value, this would appear to contradict claims that the world is experiencing conditions that are increasingly hostile to agriculture. There appears to be no negative climate change signal in this data.

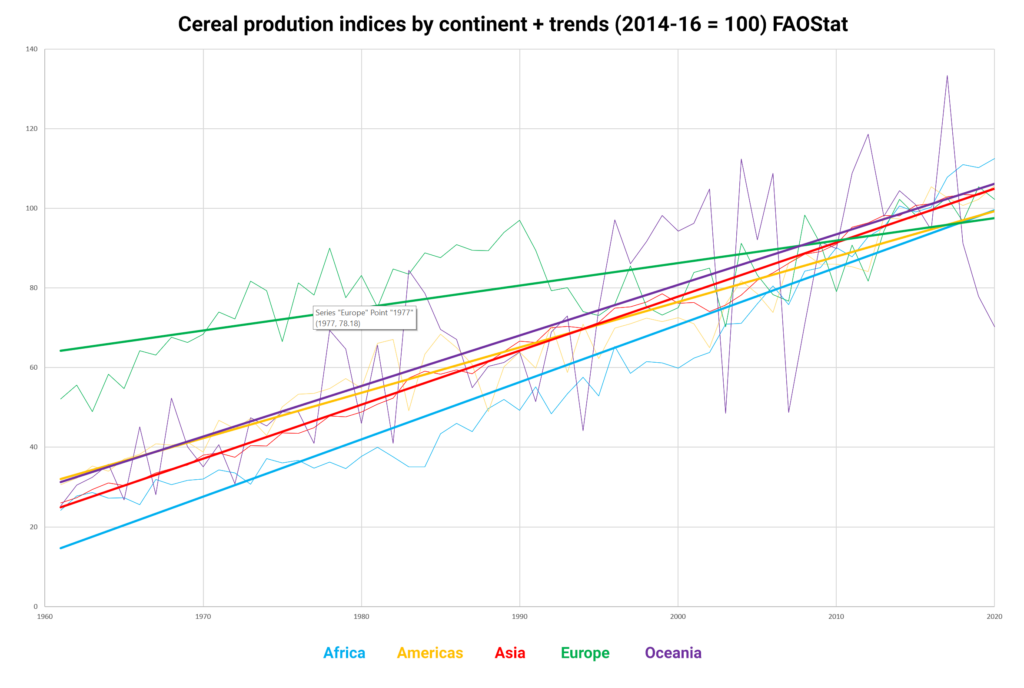

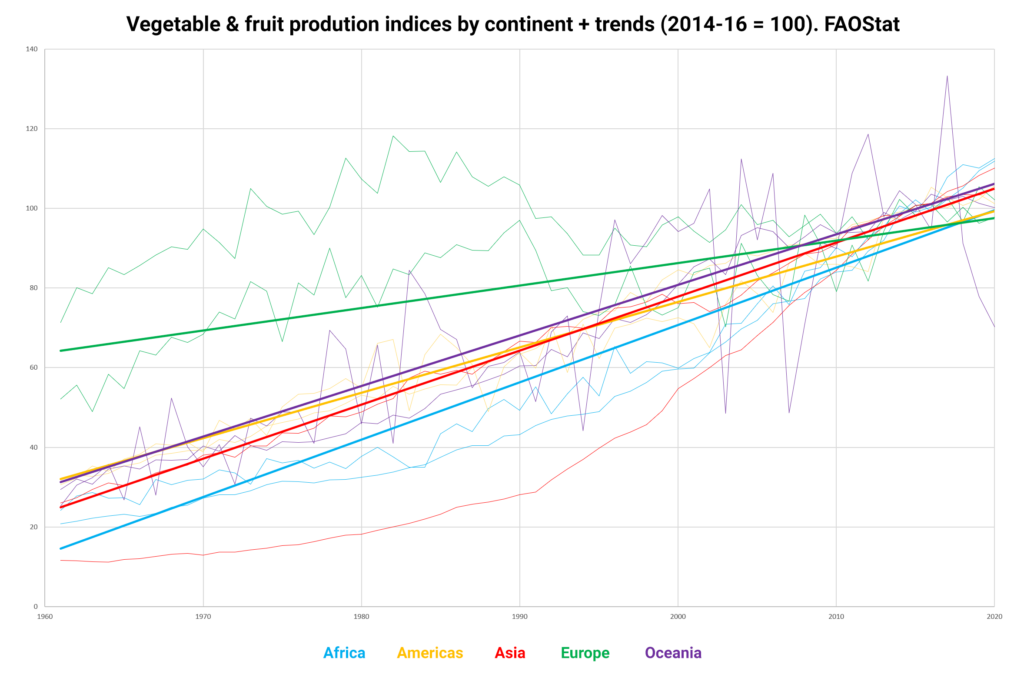

However, aggregate data of this kind can conceal more subtle changes at smaller scales, to which we may need to pay attention. At a more detailed level, though still somewhat broad, claims that the world is becoming less hospitable to society and that civilisation stands close to its destruction appear to be unfounded. There is no climate change signal in statistics representing cereal and fruit and vegetable production at continental scales. Oceania (mainly Australia) did see very significant variation in production, but the overall trend is strongly positive, and these effects may be the consequences of land management policy (see the section on wildfires). Similarly, Europe saw a decline in production through the 1990s, though this was likely the effect of EU policies intended to reduce problematic surpluses produced in the previous decade.

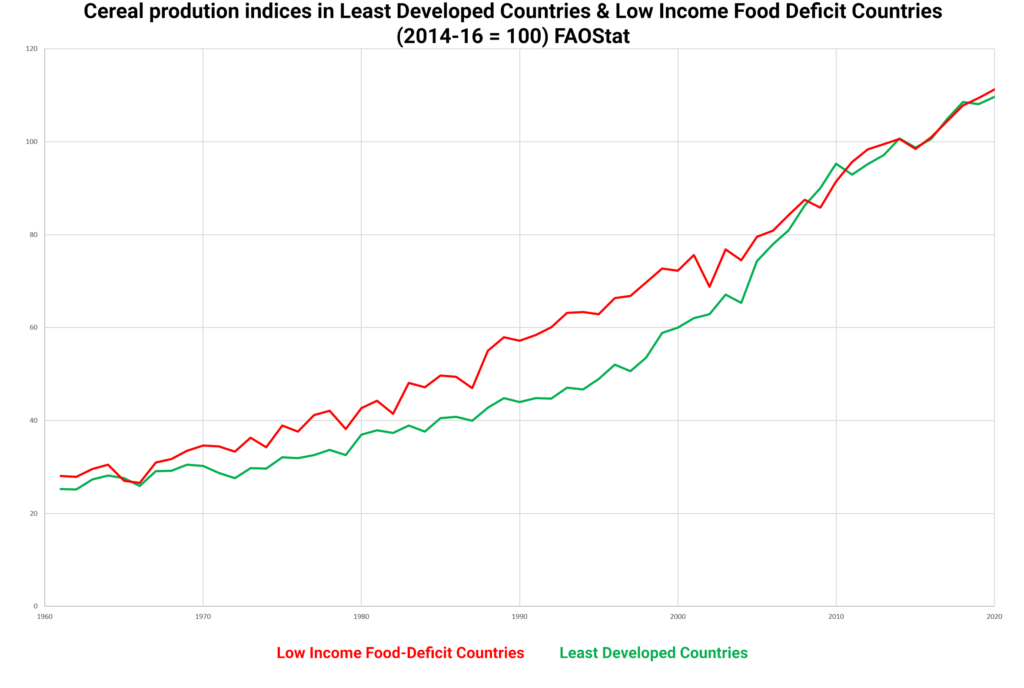

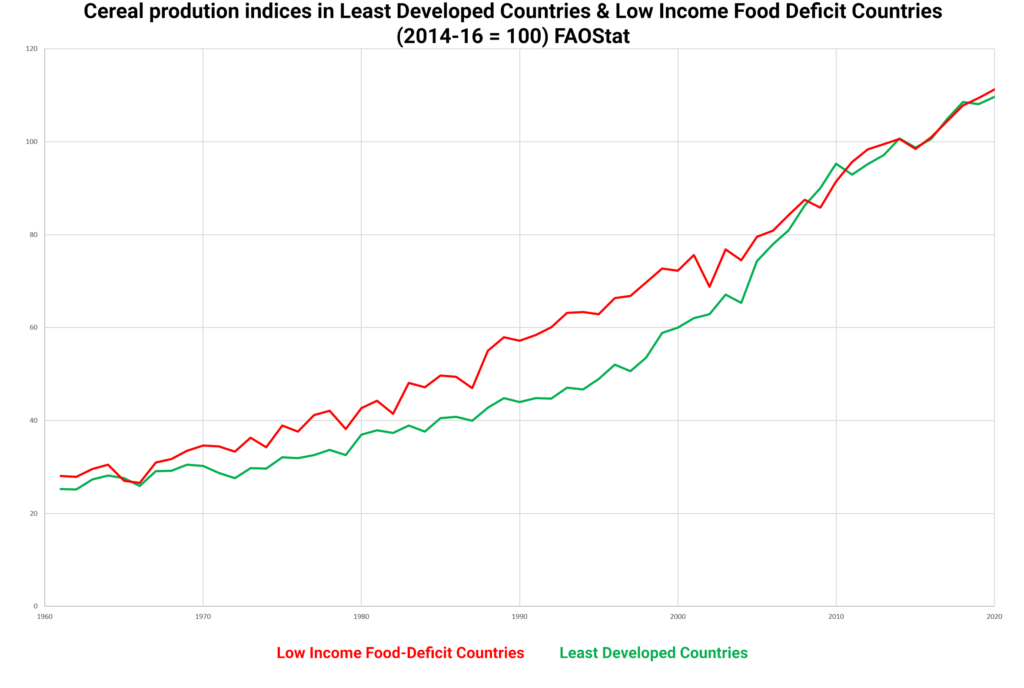

Climate change is assumed to have the greatest impact on the poorest countries, so it is in those places that we would see the most significant evidence of climate change’s impact. But as the following charts show, there is also no climate change signal in agricultural production statistics of UN groupings of Least Developed Countries and Low-Income Food-Deficit Countries.

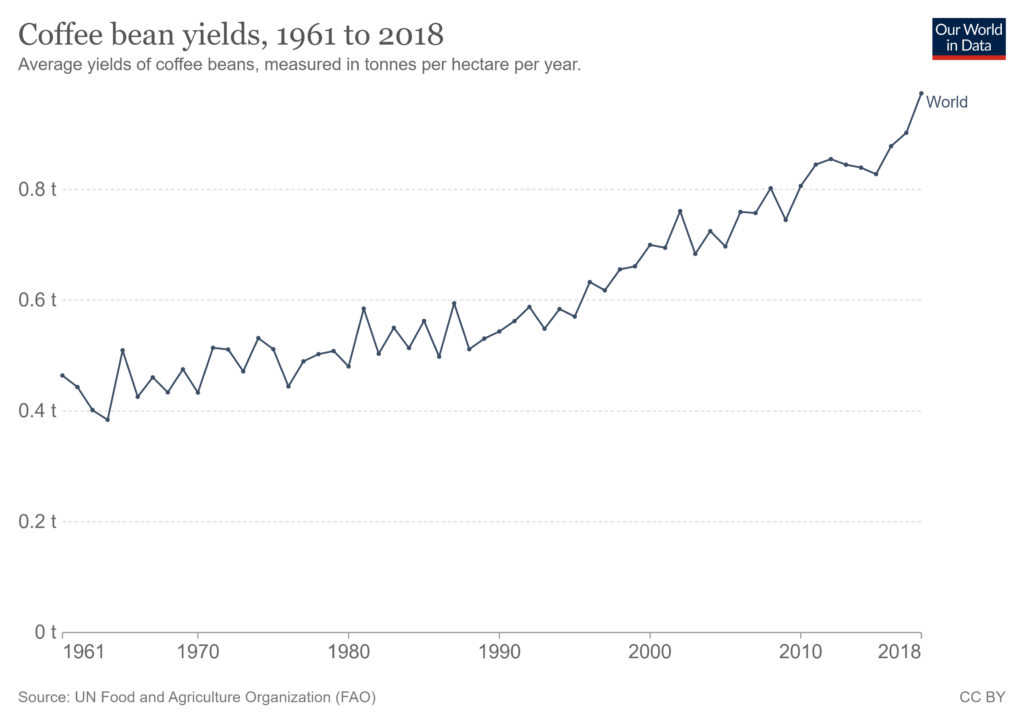

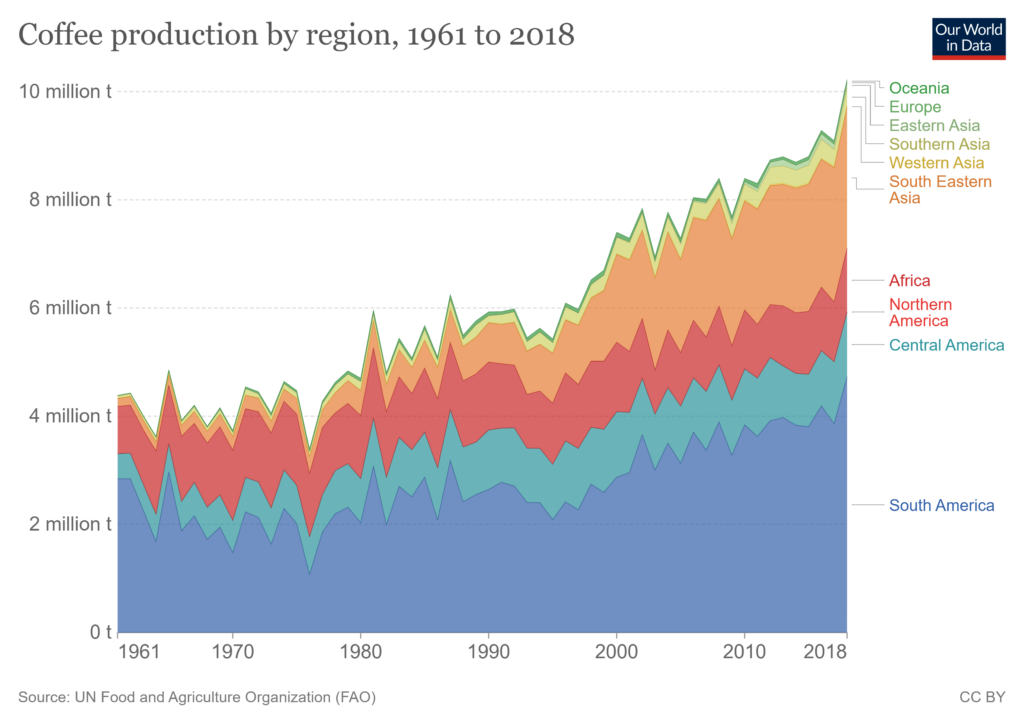

Another big fear that has been promoted by climate policy advocates is the claim that coffee, which is a highly climate-sensitive crop, is especially vulnerable to climate change, and that there is a looming “coffee apocalypse”. But again, there seems to be no negative climate change signal in global coffee production and yield statistics.

All significant coffee-producing regions seem unaffected by climate change.

It is worth observing that poorly-conceived environmental policy can have a far more devastating effect on agricultural production and on society than weather events. Sri Lanka won acclaim from international agencies and global campaigning organisations for its recent green policy agenda, which among other things banned the use of fertiliser. The policy experiment failed, leading to widespread crop failures, and reversing the country’s food self-dependency. Widespread protests ultimately led to the collapse of the government. As Nobel Prize-winning environmental economist Ted Nordhaus put it in his analysis of the affair,

The farrago of magical thinking, technocratic hubris, ideological delusion, self-dealing, and sheer shortsightedness that produced the crisis in Sri Lanka implicates both the country’s political leadership and advocates of so-called sustainable agriculture.

But the lesson of Sri Lanka’s green policy has not been learned. Following legal action against the government brought by Dutch green campaigning organisation Mobilisation for the Environment, the Netherlands has announced a similar policy of nitrogen emissions reduction which has caused farmers’ protests across the country. The Dutch government admitted that ‘there is not a future for all farmers within [this] approach’, indicating that the policy would cause some farmers to be forced off the land. Despite its own recent similar protests, Canada has announced a policy of reducing fertiliser use. At a time of rising prices, inflation, and with recession looming, these incautious interventions may create risks that are far greater for producers and consumers alike than climate change.