- Predictions made to justify ESG have not materialised.

- ESG has been a significant factor in rising energy prices.

- Despite this, such policies were being actively pursued as recently as November 2021.

In recent years, green campaigners have attempted to use financial markets to accelerate the decarbonisation of the economy. In the view of campaigners, this does not require the intervention of politics as such, but many jurisdictions including the UK, EU and USA have attempted to bring Environmental, Social and corporate Governance (ESG) principles into legislation. But from a critical perspective, using financial markets in this way is an attempt to create a form of governance which is both incautious and has likely done great harm to economies, including triggering the global energy supply crisis now afflicting millions of people.

An early stage of the green movement’s interventions in this sector was a campaign to encourage ‘divestment’ from hydrocarbon energy companies. Campaigners argued that by profiting from investments in hydrocarbon energy companies, institutions such as universities and churches had undermined their public standing – they were profiting from climate change. These institutions became the focus of intense pressure from these campaigns, and were urged to sell their assets.

A more respectable form of this campaign was developed within UK universities themselves. Researchers at an obscure, privately-funded research organisation based at Oxford University, the Smith School for Enterprise and the Environment (SSEE), developed a research programme around a hypothesis called ‘Stranded Assets’, which argued that investments in hydrocarbon energy companies would ultimately become loss-making liabilities. According to this hypothesis, a number of factors were likely to drive down the value of hydrocarbon energy assets: environmental change; policy; the falling cost of renewable energy; public opinion and political will; together with climate change litigation.

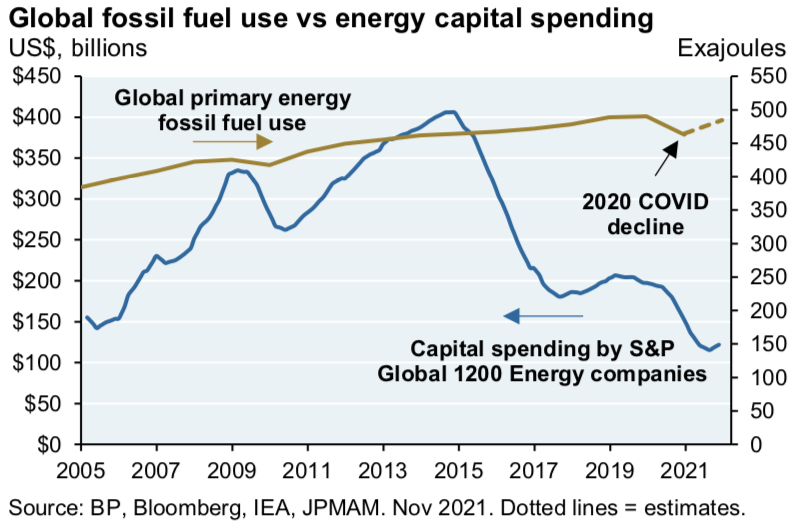

But at the time of writing, all of these claims seem to have been debunked. Demand for hydrocarbon energy has continued to increase, whereas renewable energy’s claims to lower prices have not materialised. There remains no evidence either of a ‘climate crisis’ or public opinion becoming sufficiently against hydrocarbon fuels. And public opinion is much more driven by anger at the rising cost of living caused by the energy supply crisis, which is in turn driven by green policy. Furthermore climate change litigation – lawfare – has failed in nearly every case except in a limited number of jurisdictions.

Nonetheless, the notion of Stranded Assets has been at the centre of shareholder activist campaigns and incorporated into financial institutions’ outlooks. This movement, backed with large grants by billionaire philanthropists such as Christopher Hohn and Michael Bloomberg, has created an alignment of many investors of all sizes, organised around the principles of ESG. Say On Climate, for example, is a Hohn-backed investor initiative with members in control of $14 trillion of assets, including a UK Local Authority Pension Fund with £350 billion of assets.

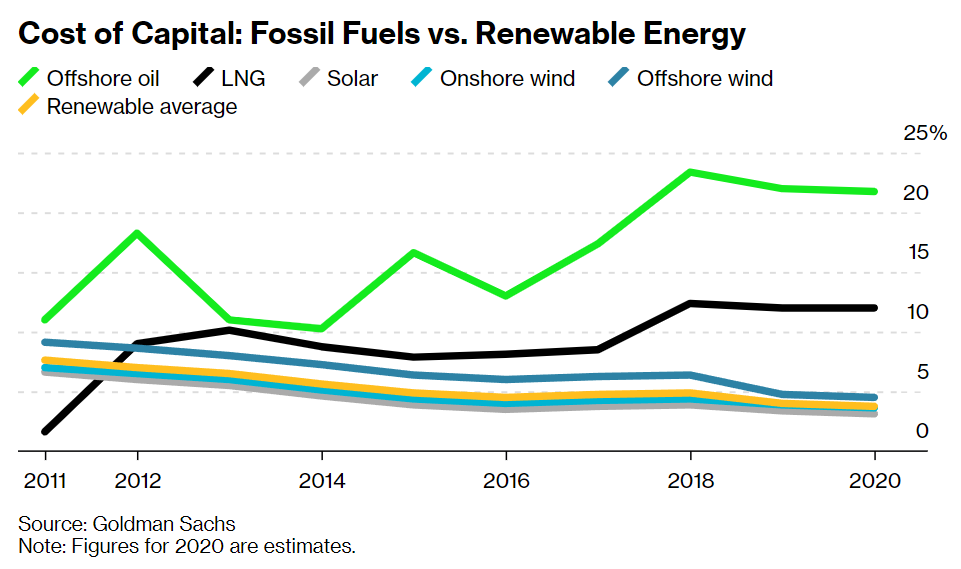

The effect of this movement is hard to quantify directly. But ESG advocates themselves, working for both Bloomberg news and Michael Bloomberg’s campaigning interests, take credit for recent shifts in the global energy and financial markets. According to a Bloomberg analyst, ‘Oil companies are finding it increasingly difficult to raise financing amid rising ESG and sustainability concerns, while banks are under pressure from their own investors to reduce or eliminate fossil-fuel financing’. This increased cost of capital has likely led to a significant underinvestment in energy production, which in turn has stalled economic recovery from covid.

ESG, however, has remained a preoccupation among Western leaders, even as unprecedented energy price rises and inflation began to grip European economies. At the COP26 meeting in Glasgow, then UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak announced that the meeting had aligned financial institutions with over $130 trillion of assets under management towards Net Zero. Former Bank of England Governor Mark Carney also made a presentation at the conference, reiterating the principles, and the necessity of moving ESG from a voluntary regulatory scheme to legislation.

ESG principles require a company to make certain disclosures about its compliance with Net Zero, such as its plan to reduce CO2 emissions. The EU has implemented its version of ESG in its ‘sustainable finance’ strategy and policies such as Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation. The US Securities and Exchange Commission is also seeking to require American firms to comply with ESG standards. And in Britain, Parliament has recently created new regulations that require ESG compliance: The Companies (Strategic Report) (Climate-related Financial Disclosure) Regulations 2022 and The Limited Liability Partnerships (Climate-related Financial Disclosure) Regulations 2022, with likely more adaptations of existing legislation on the way.

The timing of this policy throughout the West could not be more unfortunate. The effects of even voluntary ESG are now widely understood to have been detrimental and have caused criticism from within and without the financial sector. Before its recent experiment with green legislation, Sri Lanka had one of the highest ESG scores in the world. At a financial sector event organised by the Financial Times, HSBC executive Stuart Kirk openly criticised ESG, claiming that it was false at its foundation: “Unsubstantiated, shrill, partisan, self-serving, apocalyptic warnings are ALWAYS wrong”. Kirk was later suspended from his role, and subsequently resigned. Former BlackRock CIO Tariq Fancy similarly departed from the ESG trend, in a lengthy three part essay in which he accused ESG of being ‘a dangerous placebo that harms the public interest’.

As energy prices are rising, causing immense economic harm, ESG’s role in driving this problem is coming under increasing scrutiny, and should bring more focus on the parties involved. Not least implicated are the philanthropists who led the movement, and seem to have profited from it. But perhaps more culpable are the financial regulators themselves, letting themselves be influenced by green campaigning. One of the Bank of England’s main remits is to manage inflation, yet even as energy prices were clearly rising, it was advancing the notion that climate change is the greatest risk to the UKs, and global financial system, and pushing for ESG regulation. As governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney had appointed Michael Bloomberg to chair the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures – a global panel responsible for designing ESG frameworks for investors and policymakers.