- Despite alarmist claims there is little evidence that the impact of flood events is becoming more dangerous, or that globally floods are getting more frequent.

- The most significant cause of flood events is typically failure to properly maintain water management infrastructure.

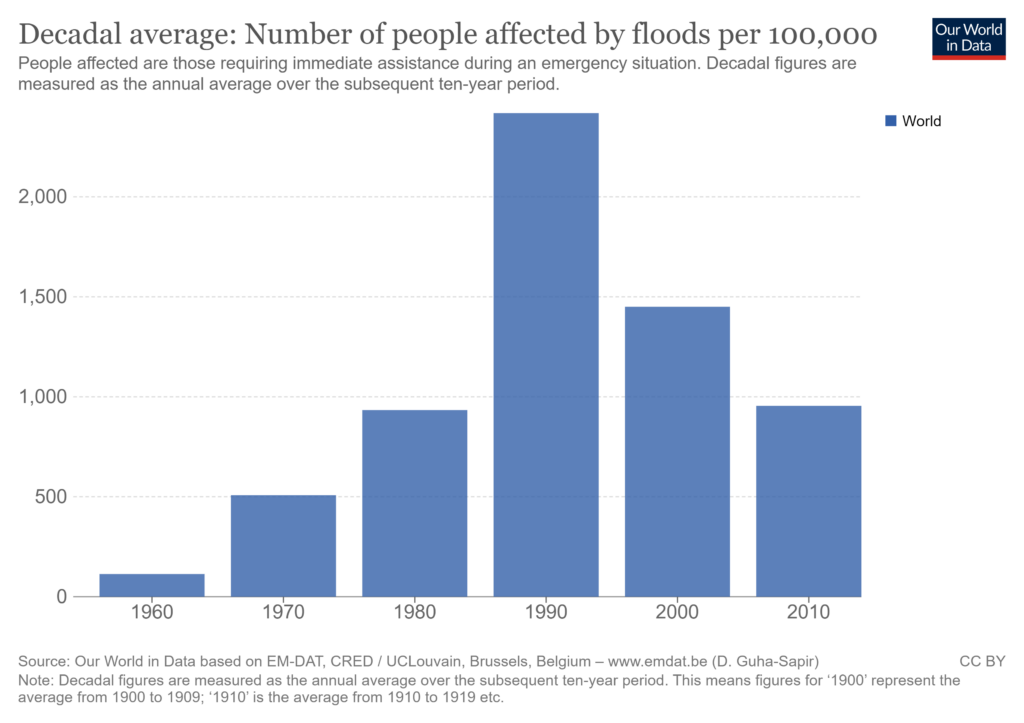

- The number of people impacted by flooding globally has been falling.

According to green claims, climate change could bring increased volumes of water to some areas, overwhelming rivers and other water management infrastructure. Flooding has always been a problem for people, particularly in older European towns and cities, which were built beside rivers and estuaries when they were important modes of transport. Historic British cities such as York and London were prone to flooding, but the rivers that flowed through them provided inhabitants with the equivalent to today’s road networks — the pain of occasional flooding was worth suffering for the opportunities. Society then began to try to mitigate the effects of flooding at times of excess water by raising banks, building new channels and diverting rivers.

The problem of flooding is as old as civilisation. But news items about flooding frequently attribute flood events to climate change as a new phenomenon, and politicians and campaigners highlight these events to argue for the urgency of climate policies. Despite this framing, there is little evidence either that the impact of flood events is more dangerous today, or that floods are getting more frequent at global scales.

A major cause of flood events is a failure to properly maintain water management infrastructure, some of which is centuries old. For example, the catastrophic inundation of New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina in 2004 was ultimately attributed to the failure of levees that had not been properly maintained, and not to the climate change which notable politicians such as Al Gore had claimed. Similarly, though not as catastrophic, flooding in England has been linked by critics of environmental policy to river management policy, though the regulator responsible for interpreting and enforcing this policy denies this criticism.

The controversy is important, not just because so many lives and so much property are at stake, but also it demonstrates the complexity belying seemingly simple conceptions of what is ‘natural’, and what is man-made. Cities and towns are better thought of as man-made structures, and so their vulnerability to the weather – and climate – are perhaps better understood as shortcomings of their design than as features of the natural landscape. In July 2021, heavy rains brought floods to western Germany, particularly around the district of Ahrweiler, killing nearly 200 people and destroying many properties. Such a catastrophe drew international news coverage, a great deal of which immediately framed the tragedy in terms of climate change. The questions of whether or not the rainfall that caused the floods was unprecedented, and whatever contribution was made by anthropogenic climate change, are arguably irrelevant and perhaps even a cynical distraction. Both the extreme rainfall and the floods were predicted and a warning was issued to local authorities by the European Flood Awareness System (EFAS) days in advance, but the authorities failed to act. It was a failure of human systems – policy – and of the design of civil infrastructure and planning that failed to mitigate a predictable and predicted episode of extreme weather, not the extreme weather itself which is responsible for the catastrophe.

Such events, from Katrina to the floods in western Germany, should overturn our understanding of a ‘natural disaster’. Nearly every case of significant loss of life and damage to property seemingly caused by extreme weather-induced flooding in the wealthier parts of the world (i.e. the west) is a failure of design and policy. And similarly, where such events occur in emerging or developing economies, it is the want of better systems of governance, wealth and infrastructural development that are the causes of vulnerability to extreme weather. These things are better understood, first as a historical fact of life, and second as problems that we have become much better at dealing with over recent decades. But these approaches contrast excited media coverage of extreme weather and its putative links to climate change.

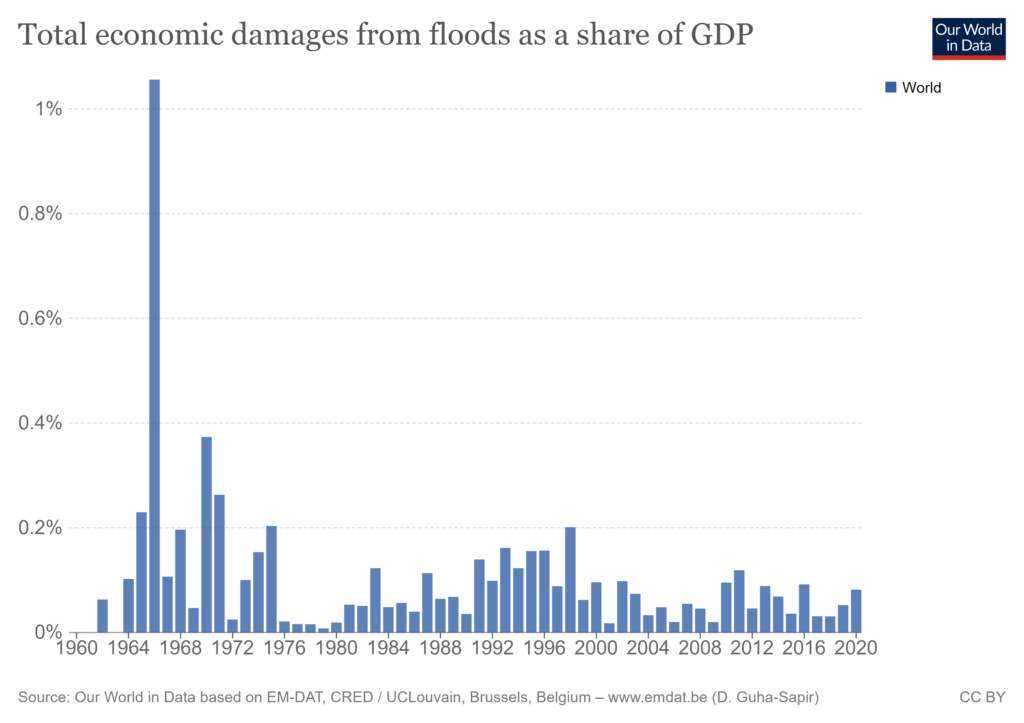

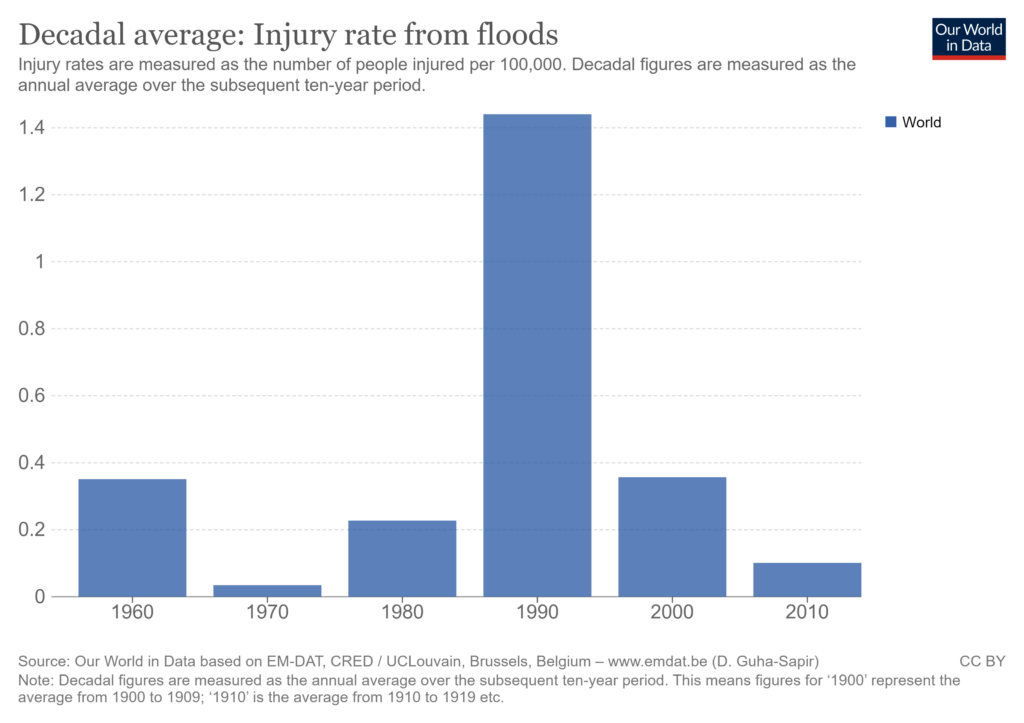

As the following charts show, risk of injuries from flooding at the global scale are extremely small (deaths from flooding are virtually zero) and falling, the number of people affected by flooding has fallen, and the economic damage caused by flooding is falling. Moreover, this data, compiled by EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium showing the impact of flooding disasters, does not adjust data for effects such as GDP and population growth, or improved reporting capacity. When such adjustments are made (‘normalisation’), an even more positive picture of late 20th Century human development images, as is discussed in Column 3.

IPCC AR6 WGI also contradicts many alarmist stories in the news media that attempt to link catastrophic flooding events to climate change. The report points out that ‘heavier rainfall does not always lead to greater flooding’, meaning that there is no causal or detected relationship between increased rain and floods, and that ‘there is low confidence in the human influence on the changes in high river flows on the global scale’.