- The influence of global warming on glaciers and ice sheets may have been detected, but it is frequently very significantly overstated.

- There is clear evidence of political narratives being put ahead of scientific research.

- Some researchers have tried to bring a more sober perspective to the debate.

Glaciers and ice sheets (rather than sea ice as such) melting is one of the major concerns about global warming and its consequences. Whereas Arctic sea ice cannot contribute to sea level rise, water locked up in the world’s glaciers and ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica contain enough water to raise sea levels by 70 metres. During the last ice age, so much water was locked up in these sheets that sea level was more than 100 metres lower. Given such a huge range of potential sea level, and such sensitivity of glaciers to global temperatures, it would be foolish not to take these concerns seriously.

However, a number of alarmist and misleading claims about the imminence of glacial and ice sheet collapse, and their sensitivity to anthropogenic warming, have come to prominence in mainstream discussions about climate change in recent years. Ice ages and interglacial episodes were driven by radical changes, which are not necessarily equivalent or comparable to changes caused by anthropogenic CO2 emissions.

Al Gore’s 2006 film An Inconvenient Truth highlighted the plight of the world’s glaciers, and in particular made the receding white peaks of Kilimanjaro a symbol of climate change. And this symbolisation has driven much climate scepticism. Unfortunately for Gore, much of what he claimed in the film was simply not true.

Researchers have pointed out before and since Gore’s film that the apparent decline of white peaks and glaciers such as Kilimanjaro’s is not due to warming as much as local changes to the natural environment and climate. Simply put, less snow fell on the mountain, and this change was driven by variability in the weather systems, though not significantly anthropogenic in origin. Other studies have suggested that these broader weather system changes have been amplified by regional land-use changes, such as deforestation, which is an anthropogenic input, but not man made climate change, in the usual sense.

A second failed symbol of climate change was the prediction of the loss of glaciers from Glacier National Park in the USA. Gore echoed a claim that the park’s glaciers would be gone ‘within fifteen years’. However, though substantial reductions in the size of these glaciers was recorded between 1966 and the time of Gore’s movie, a much less radical recession has been observed more recently.

However, these glaciers’ existences are more symbolic than the catastrophe that they seemingly herald. A more troubling prediction from Gore’s film concerned the Himalayas.

In the Himalayas there is a particular problem because 40% of all the people in the world get their drinking water from rivers and spring systems that are fed more than half by the melt water coming off the glaciers. Within this next half century those 40% of the people on Earth are going to face a very serious shortage because of this melting.

This claim emerged around the same time as an IPCC report that claimed that the Himalayan glaciers could disappear by the year 2035.

Glaciers in the Himalaya are receding faster than in any other part of the world […] and, if the present rate continues, the likelihood of them disappearing by the year 2035 and perhaps sooner is very high if the Earth keeps warming at the current rate. Its total area will likely shrink from the present 500,000 to 100,000 km2 by the year 2035 (WWF, 2005).

This claim was subsequently disputed by the Indian government, whose Environment Minister criticised the IPCC report as ‘alarmist’, and produced the government’s own analysis. Flamboyant late IPCC chair, Rajendra K. Pachauri, replied, calling the Indian government’s position “voodoo science” and “extremely arrogant”, doubling down on the IPCC’s scientific authority and its status. However, a subsequent internal IPCC investigation revealed that the source of the claim was not scientific research but a 2005 report by green NGO, the WWF. This claim was attributed in turn to a 1999 New Scientist article:

All the glaciers in the middle Himalayas are retreating,” says Syed Hasnain of Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, the chief author of the ICSI report. A typical example is the Gangorti glacier at the head of the River Ganges, which is retreating at a rate of 30 metres per year. Hasnain’s four-year study indicates that all the glaciers in the central and eastern Himalayas could disappear by 2035 at their present rate of decline.

According to a Guardian article that summarised the affair, the author of the claim, Syed Hasnain had been speculating. But it also emerged that Hasnain was a senior fellow at The Energy and Resources Institute, whose director was Pachauri. Similarly coincidentally, the author of the Guardian article happened also to be the author of the 1999 New Scientist article that had quoted Hasnain, arguably without due care.

The problem this affair exposed was that it is difficult, even for a major national government, to challenge what appeared to be the leading scientific authority on the issue, despite its manifest failure. Yet it was not so difficult for a ‘speculative’ and categorically alarmist claim to be elevated to the status of “scientific fact”: an uncorroborated statement to a popular science magazine, cited by a political campaigning organisation, was then cited by an IPCC author. The IPCC subsequently held an investigation into its review practices, which improved the use of what was called at the time “grey literature” – non-scientific and non-peer-reviewed articles, typically published by campaigning organisations. However, it is not so clear that the problems of nepotism and credulity towards certain political narratives, within and beyond the IPCC, are so easily dealt with.

There has been substantial debate on the question of glaciers’ sensitivity to climate change, which many have observed, like sea ice, glaciers are in remote and hostile areas and are extremely dynamic geographic features, the history of which is often lost or omitted from more alarmist interpretations. Regarding Al Gore’s claims that “40% of all the people in the world get their drinking water” from Himalayan glaciers and that those people “are going to face a very serious shortage because of this melting”, for instance, a 2009 article in Science pointed out that in fact “Glacier melt contributes 3% to 4% of the Ganges’s annual flow”, and that monsoon rainfall accounts for the majority. It is difficult to understate the magnitude of Gore’s error, which misled his audiences into believing that 3.1 billion people face a future without water, whereas the figure lies much closer to zero. Not only have the vulnerabilities of glaciers been overstated, but so too have the impacts of any possible change. 3.1 billion people’s futures are much safer than Gore claimed.

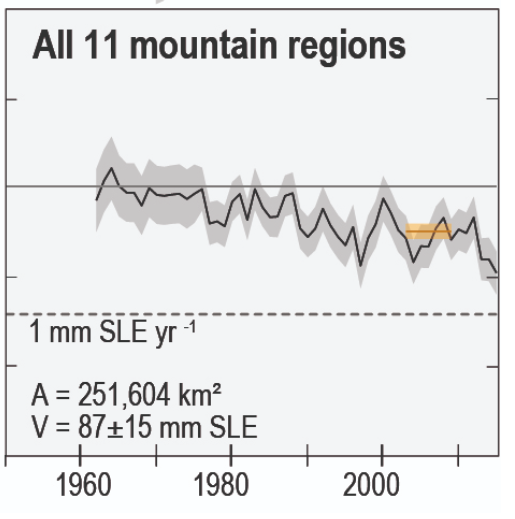

But are glaciers growing or shrinking, and what role is global warming playing? The IPCC’s 2022 Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (Ch. 2.2.3) finds that “It is very likely that atmospheric warming is the primary driver for the global glacier recession” and that “There is limited evidence … that human-induced increases in greenhouse gases have contributed to the observed mass changes”. In estimating the human contribution, the IPCC found that “the anthropogenic fraction of mass loss of all glaciers outside Greenland and Antarctica increased from 25 ± 35% during 1851–2010 to 69 ± 24% during 1991–2010”. This loss, from the mountain glacier ranges under the IPCC’s consideration, is equivalent to less than 1mm of sea level rise (marked as SLE in the below chart) per year.

Care must be taken to observe that the IPCC’s estimates offer an extremely wide range, reflecting scientific uncertainty (i.e. “limited evidence” from which to draw scientific conclusions). “25 ± 35%” equates to a range of between -10% and 60%, and “69 ± 24%” equates to a range of 45% to 93%. Arguably, these wide ranges make the estimates functionally useless for the purpose of direct attribution, though also arguably may be useful in identifying a trend of glacial recession becoming increasingly influenced by anthropogenic causes.

Care is also required to observe that although the two eras identified by the estimates overlap and one begins in 1851, the longer trend encompasses an era that is not characterised by global warming. And this reflects a limitation of nascent climate sciences, and the study of glaciers and ice sheets in particular, similar to the problems of estimating sea ice loss in the Arctic. The focus of the IPCC’s analysis is from the middle of the 20th Century onwards. Though this may be for good reasons (such as data quality), historical evidence may challenge inferences drawn from the IPCC’s headline conclusions.

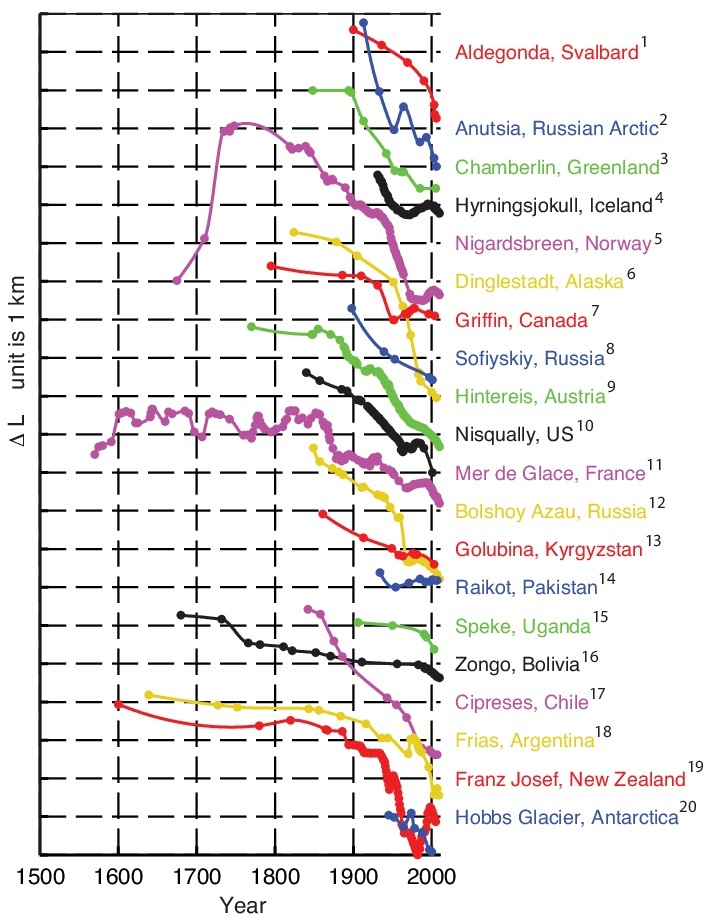

Though the IPCC’s estimates cite a study which compares mid-19th onward and late twentieth to early 21st century trends in glacial recession, other studies find the opposite conclusion. For example, one 2014 study that examines records stretching as far back as the 16th Century found: “The retreat was strongest in the first half of the 20th century, although large variability in the length change of the different glaciers is observed”.

This, also, should not be read as a conclusive rebuttal to claims about anthropogenic global warming’s effects on glacial extent. What it should do, however, is alert to the fact that glaciers, like sea ice, are extremely dynamic, and are sensitive to a number of forces including, seemingly, global temperature, but also local climate variability and land use.

Of greater concern than mountain glaciers, whose significance, like sea ice, is largely symbolic, are the substantial ice sheets in Greenland and the West Antarctic. Both regions have become the focus of significant controversies and debates, not merely between climate change sceptics and their counterparts, but also within seemingly mainstream science.

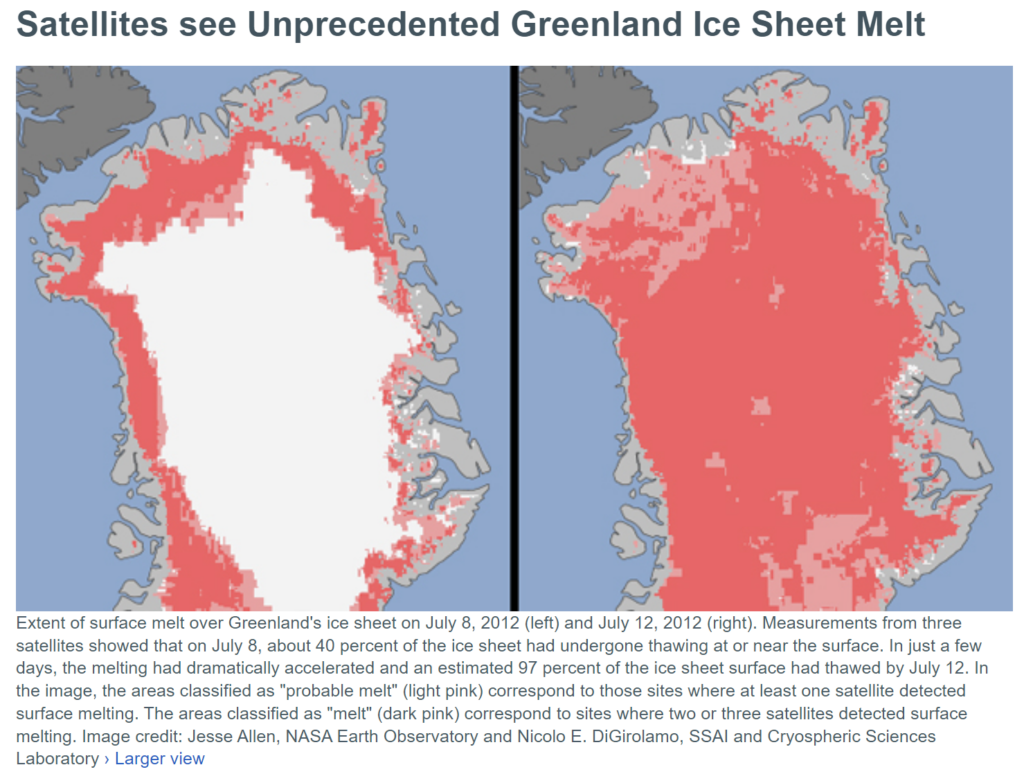

In 2012, a NASA JPL press release announced that “Satellites see Unprecedented Greenland Ice Sheet Melt”. The press release cited a researcher stating that the phenomenon was consistent with historical observations: “melting events of this type occur about once every 150 years on average” and that “With the last one happening in 1889, this event is right on time”. But this caution, located at the bottom of the text, was contradicted by the headline’s misleading use of the word ‘unprecedented’. Consequently, countless headlines were produced, prompting Malte Humpert from the Arctic Institute Centre to publish a corrective:

The Greenland ice sheet, which is up to 3000+ meters thick, is not “melting away”, did not “melt in four days”, it is not “melting fast”, and Greenland did not “lose 97% of its surface ice layer”. Instead Greenland surface ice experienced thawing or melting across 97% of its area, most of which quickly refroze, especially at higher elevations. Only near the coast did some melt water drain into the ocean.

This was a welcome intervention by climate science, cautioning a globally-respected scientific organisation against using terms like “unprecedented”, and noting that the unhelpful news stories it had generated. However, a decade later, this lesson had not reached all scientists studying the cryosphere. In August 2022, Nature Climate Change (NCC) published an article that proclaimed an “ominous prognosis for Greenland’s trajectory through a twenty-first century of warming”. The study used a computer model of Greenland’s ice sheet to predict that no matter what policies were implemented to try to stop climate change, “at least 274 ± 68 mm” but as much as “782 ± 135 mm” of future sea level rise has already effectively been caused. Again, countless dramatic headlines were produced.

What the authors of such headlines typically fail to understand, and the authors of the studies forget to explain to them, is that the art of computer simulations of this kind do not have a robust history of success. They are mathematical projections, which can be misleading, and seem to have greater political utility than applications in scientific understanding. Cool, scientific objectivity is rarely expressed as “ominous prognosis”.

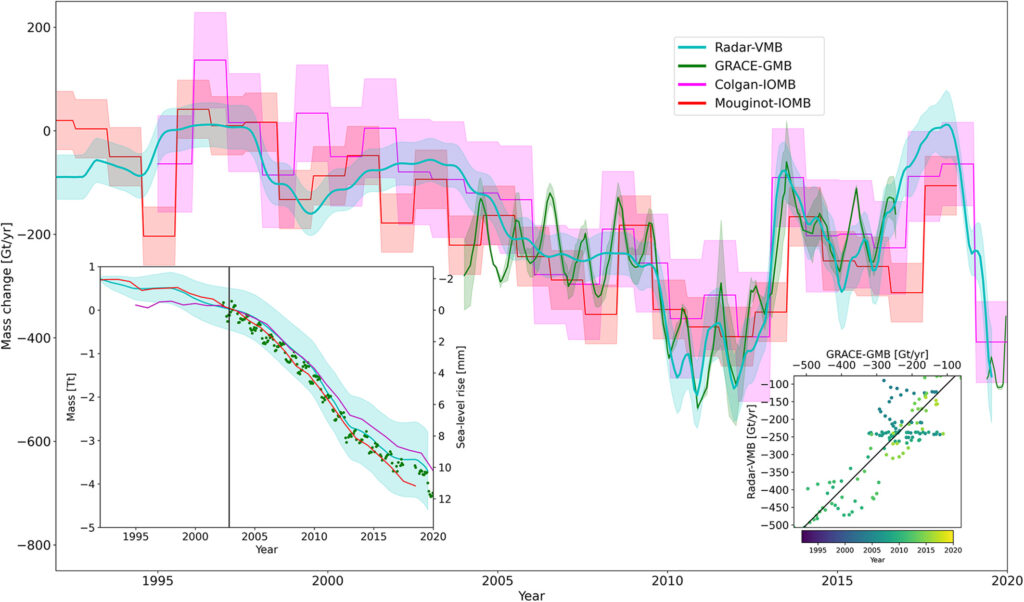

Comparisons with observational records are more helpful. A 2021 study published in Geophysical Research Letters (GRL), based on satellite data, found a loss of mass from the ice sheet equivalent to a “sea-level rise contribution of 12.1 ± 2.3 mm from the ice sheet since 1992”. At such a rate, the NCC study’s lower estimate of mass loss (274mm) would take 685 years, and the upper estimate (782mm) would take nearly 2,000 years. Though the GRL study argues that some acceleration in the rate of ice loss was observed, it also demonstrates considerable changes in the rate of loss, from a clear trend starting in the late 1990s to around 2013. This was followed by a short trend towards zero net loss, which is again followed by a rapid reversal of this trend, indicating significant natural variability. Modelling studies may therefore be unduly dramatic and prematurely pessimistic.

The IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (Ch. 4 Table 4.2) uses “process-based modelling studies” to make projections of Greenland ice sheet loss contributions to global sea level rise between 2000 and 2100, using three policy-based scenarios (Representative Concentration Pathways, RCPs). For the lowest scenario (RCP 2.6), the IPCC predicts between 40 and 100mm of sea level rise, and between 70 and 210mm for the highest (RCP 8.5). However, again, care should be taken to observe that these projections are produced from computer simulations, do not compare well with observations, and depend on the circular reasoning underpinning the policy-based RCP scenarios

Similarly dramatic stories have been centred around the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS). Many scientists suspect that WAIS is already unstable, and therefore especially prone to climate change. News articles from 2014 report scientists’ concerns that anthropogenic climate change had caused WAIS melting, triggering an irreversible process in the wider region that could contribute up to 3.6 metres to sea level rise. A 2018 article in Science amplified these concerns, stating that, “the world may need to prepare for sea level to rise farther and faster than expected”, and that a recent study of WAIS’s historical contribution to sea level had found that “ocean waters rose as fast as some 2.5 metres per century”.

The IPCC (Ch.4.2.3.5) cites a range of potential outcomes for the future WAIS, highlighting disagreements within science on the glaciers that make up the WAIS, for example highlighting “key uncertainties” about the WAIS’s structure: “Whether the [Thwaites glacier’s] retreat is driven by ocean changes driven by climate change or by climate variability […] is still under debate”. Similarly, “computational complexity” confounds a clear projection as “results are critically dependent on initial conditions, sub ice shelf melt rates, and grid resolution”. One cited study finds “projected contribution of WAIS was found to be limited to 48 cm in 2200”, and another that “a full West Antarctic retreat does not occur with limited oceanic heating under the two major ice shelves”.

These findings of uncertainty in relation to the WAIS’s future would seem to contradict more categorical alarmist scenarios presented to the news media. However, the IPCC Special Report itself is not against emphasis on alarmist projections:

A worst-case scenario was explored with an intermediate complexity climate model coupled to a dynamical ice model […], in which all readily available fossil fuels are combusted at present-day rates until they are exhausted. The associated climate warming leads to the disappearance of the entire AIS with rates of [sea level rise] up to around 3 m per century.

But the inclusion of such studies raises the question of the seriousness of the IPCC’s analysis. The complete exhaustion of all available fossil fuels is not a plausible scenario. And this magnitude of loss implies at least a tenfold increase in the observed rate of loss. Moreover, the coupling of untested simulations multiplies, causing error to cascade through the exercise, inevitably only to produce alarmist conclusions. The only purpose of such studies, with no test in reality, can be to drive political narratives.