- Despite immense media attention linking wildfires to climate change, considerable debate exists about whether any link exists.

- Data from observations suggests that wildfires have not increased globally in recent years.

- Science does not properly distinguish between the conditions that cause wildfire and the outbreak of wildfire.

Each summer, fresh images of extensive damage done to forests and homes by wildfire ignites media panic and speculation about the role of climate change in these apocalyptic scenes. But areas from which these images are produced, such as California and Australia, are typically places that have always been prone to significant wildfire.

Moreover, it is development – population growth – that brings rightful focus to these human interest stories in regions that were previously considered hostile to human settlement. California, for example, had a population of just 3.4 million in 1920. By 2020, it had a population of 39.4 million. And its wealthier population enjoy homes in more rural locations, closer to forests. Similarly, sceptics have pointed to changes in forest management policy in recent decades, in which the practice of controlled burning or other measures to reduce the ‘fuel load’ has been discouraged.

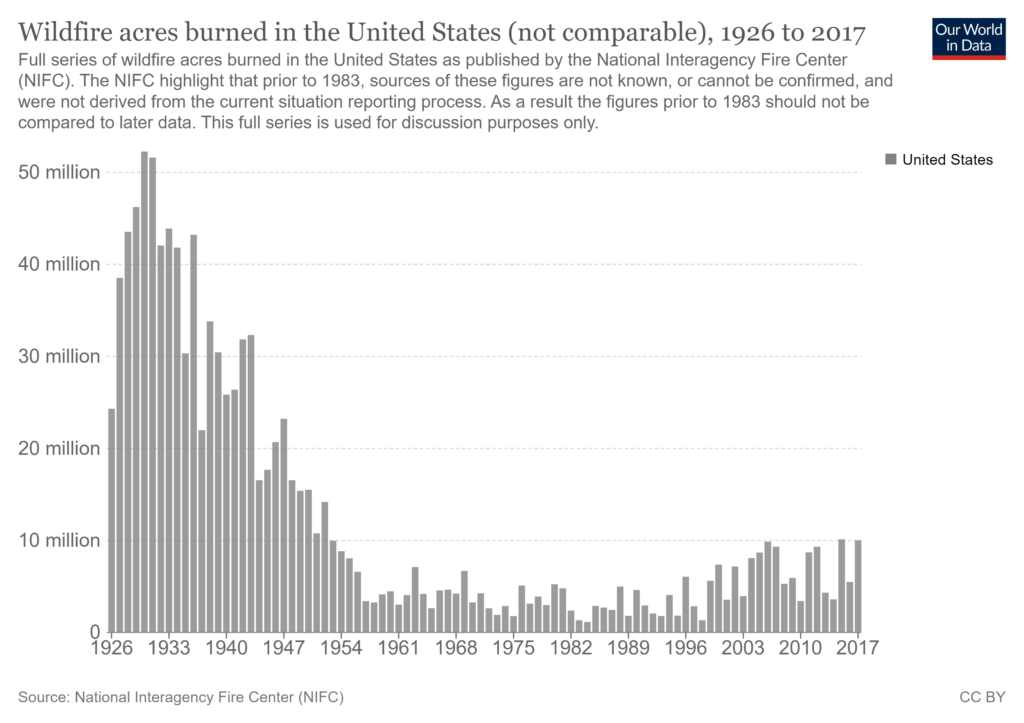

And there are convincing arguments that the scale of wildfires was much greater in the past. For example, statistics showing wildfire extent in the USA show that the first half of the century was a far more dangerous time.

However, some responses to this observation either omit the earlier data entirely, to claim that the quality of wildfire data in the past is too low to compare to more recent history, and emphasise statistics from the 1960s onwards instead. This later era appears to show a trend of increasing wildfire extent from the 1990s to the 2010s, causing controversy between these two approaches, lending significant weight to sceptics’ argument that inconvenient data has been omitted.

Data from the more recent satellite era also casts doubt on the way the issue is presented in news coverage. A 2017 study published in Science ‘found that global burned area declined by 24.3 ± 8.8% over the past 18 years’, and that model-based predictions ‘may overestimate fire emissions in future projections’ of the impact of climate change in promoting wildfire. This study followed a 2016 study which addressed ‘widely held perceptions both in the media and scientific papers of increasing fire occurrence, severity and resulting losses’ directly, finding that ‘the quantitative evidence available does not support these perceived overall trends’, that ‘global area burned appears to have declined overall over past decades, and there is increasing evidence that there is less fire in the global landscape today than centuries ago’.

These studies, reproduced by others, present a radically different picture of the world, compared to mainstream coverage, which is now a routine part of the annual news cycle. Wildfires, though devastating to human settlements, are a natural process, and part of many forests’ and grasslands’ life-cycle. This fact has simply not been reported by news media, nor acknowledged by policymakers, perhaps because fires are so devastating that to concede that wildfires are a natural process means taking responsibility for policies to protect people and property from them, whereas climate change may be a convenient excuse for policy failure.

When wildfires have struck in rural Australia, commentators noted that fire management policies had changed in recent years. Whereas some administrations used to practice controlled burning more routinely, continuing from aboriginal land management, this seemed to conflict with environmental priorities such as conservation and climate change mitigation. This has led to intense debate across the country, some blaming the Australian government’s apparent disinterest in climate change for bushfires, and others blaming land management policy failure. As with many extreme weather phenomena, the influence of policy in areas which are prone to wildfire outbreaks appears to be of much greater significance than the weather itself.

IPCC AR6 WGI finds that

There is medium confidence that weather conditions that promote wildfires (fire weather) have become more probable in southern Europe, northern Eurasia, the US, and Australia over the last century.

But ‘fire weather’ is not the same as fire. ‘Fire weather’ is a category of weather that is presumed to create conditions that make wildfire more likely, such as drought. But whereas this measure of ‘risk’ seems to have increased according to the IPCC, it does not seem to have resulted in a greater number or extent of wildfires. Thus, the category of ‘fire weather’ is problematic. If a phenomenon happens less often, then by definition, the risk of that phenomenon has decreased.